Retinal Artery Occlusion: Cause and Treatment.

A retinal artery occlusion is a rare condition that may cause severe vision loss. There are two main types of retinal artery occlusion: branch and central retinal artery occlusions.

There are no proven medical or surgical techniques to treat retinal artery occlusion, but their presence indicates an underlying systemic cause that must be diagnosed and treated. For instance, if the disorder is caused by giant cell temporal arteritis, an immediate intravenous steroid is required to lessen the chance of vision loss in the other healthy eye. The only eye treatments that may be used are laser or intravitreal anti-vascular endolthelial growth factor injection. This is done if abnormal blood vessels (neovascularization) develop and cause complications such as glaucoma.

Retinal Vein Occlusion: Cause and Treatment.

Two Different Forms of Blockage.

Retinal vein occlusion is a relatively common cause of vision loss. The condition takes two forms: branch retinal vein occlusion and central retinal vein occlusion. Despite some similarities, these two conditions differ in terms of risk factors, treatment and visual prognosis.

Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO)

What you need to know:

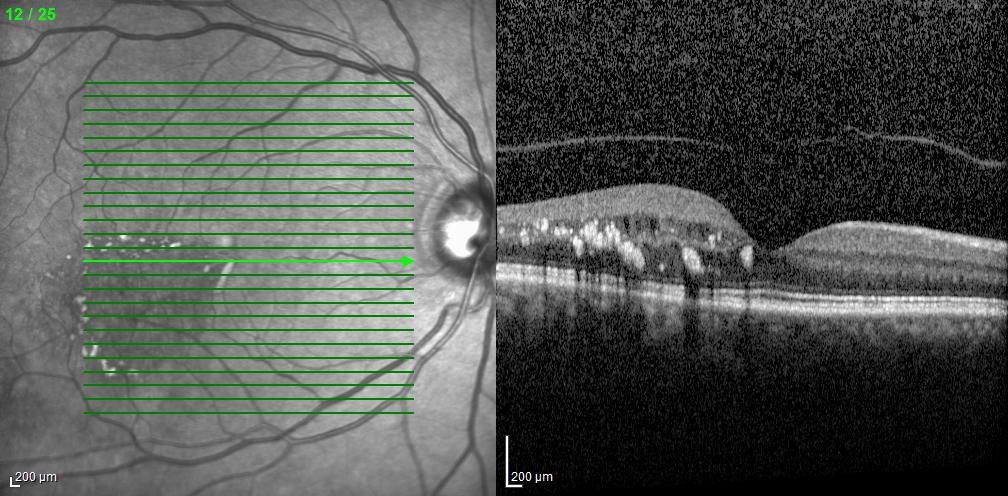

The retinal artery supplies blood to the retina. The blood flows through retinal arterioles, capillaries, and finally through branch retinal veins that drain into the central retinal vein. A branch retinal vein occlusion occurs when part of this branch vein system is blocked. A blockage causes backpressure and leads to hemorrhaging, exudation, and/or decreased blood flow in the area of the retina drained by that particular branch retinal vein. Below is an Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) image of a BRVO with Macular Edema.

How do branch retinal vein occlusions affect vision?

Branch retinal vein occlusion can affect the vision in a number of ways. Poor blood flow (ischemia) through the center of the retina (macula) can severely limit vision. Additionally, exudation and bleeding from the capillaries can cause swelling or edema in the macula, which leads to visual loss. Poor blood flow can also lead to development of abnormal new vessels not only in the retina, but also in the front part of the eye. This is known as rubeosis iris. These new vessels can cause bleeding in the eye (vitreous hemorrhage) and/or increased eye pressure (neovascular glaucoma). In rare instances, scar tissue can form on the surface of the macula, causing macular pucker formation. In extremely rare but severe cases, an individual may develop a retinal detachment.

Who is at risk of developing branch retinal vein occlusion?

Branch retinal vein occlusion typically occurs after age 50, with peak incidence between ages 50 and 70. Individuals with a history of systemic hypertension, history of stroke or coronary artery disease, history of smoking, and history of glaucoma are at an increased risk for developing this condition. Rarely, blood clotting abnormalities or certain types of uveitis can predispose to the development of branch retinal vein occlusion.

What is the risk to the other eye?

Almost 10% of patients with branch retinal vein occlusion develop a central retinal vein occlusion or branch retinal vein occlusion in the other eye.

How is branch retinal vein occlusion treated?

Branch retinal vein occlusion is easily diagnosed with an examination. However, in the first 3-6 months following its incidence, significant intraretinal hemorrhages can make it difficult to predict its course and visual outcome. Once the intraretinal hemorrhages clear, a fluorescein angiogram is usually performed to look for areas of abnormal leakage or poor blood flow within the macula. If poor blood flow is diagnosed, the chances of visual improvement are limited and there are few treatment options. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections in the eye are currently the first line of treatment for the macular edema, injections of steroids such a Ozurdex is used as a alternative or in combination therapy for chronic macular edema, while laser continues to be the treatment of choice for neovascularization due to retinal vein occlusions. If abnormal new vessels (neovascularization) develop, laser treatment will cause regression of these abnormal vessels. For persistent vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment or macular pucker formation, surgery might be necessary.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO)

What you need to know:

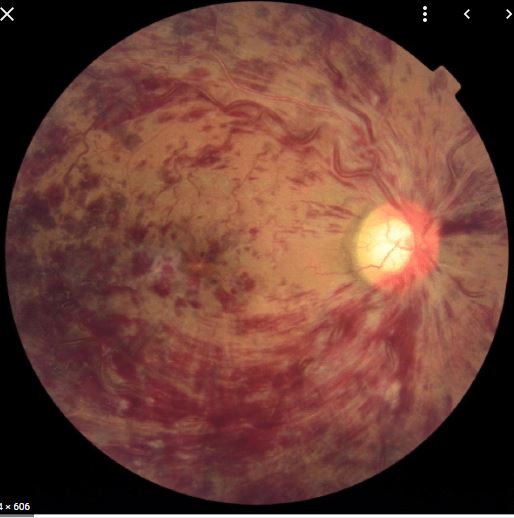

The retinal artery supplies blood to the retina. Blood flows through the small arterioles and capillaries and finally leaves the retina through the central retinal vein. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion is a blockage in the central retinal vein that causes backpressure and leads to bleeding, leakage and/or decreased blood flow in the retina.

How does central retinal vein occlusion affect vision?

Central retinal vein occlusions can affect the vision in a number of ways. Poor blood flow (ischemia) through the macula can severely limit vision. Additionally, exudation and bleeding from the capillaries can cause swelling in the macula, which leads to visual loss. Poor blood flow can also lead to development of abnormal new vessels not only in the retina, but also in the front part of the eye (rubeosis iridis). These new vessels can cause bleeding in the eye and/or increased eye pressure (neovascular glaucoma). In rare instances, scar tissue can form on the surface of the macula, causing macular pucker formation. Another rare complication is retinal detachment.

Are there different types of central vein occlusion?

There are two types: ischemic and non-ischemic central vein occlusion. Non-ischemic generally has good blood flow and a favorable visual prognosis. However, one-third of patients with the non-ischemic condition develop ischemia over time. That’s why careful follow-up is recommended for early detection.

Who is at risk of developing central retinal vein occlusion?

Central retinal vein occlusion most commonly occurs after age 50. Systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus and open angle glaucoma are important risk factors. Blood clotting abnormalities are especially important in patients younger than age 50. Rarely, uveitis and certain infections may lead to central retinal vein occlusion.

What is the risk to the other eye?

Almost 10% of patients with central retinal vein occlusion develop a central retinal vein occlusion or branch retinal vein occlusion in the other eye.

How is central retinal vein occlusion treated?

Central retinal vein occlusion is easily diagnosed upon examination. However, in the first 3-6 months following central vein occlusion, significant intraretinal hemorrhages can make it difficult to predict the course and visual outcome. In general, the better the vision is at the time of diagnosis, the better the prognosis. Once intraretinal hemorrhaging clears, a fluorescein angiogram is usually performed to determine whether the central retinal vein occlusion is ischemic or non-ischemic. Laser treatment is not effective for macular edema from central retinal vein occlusion. If abnormal new vessels (neovascularization) develop, laser treatment is usually performed. For persistent vitreous hemorrhages, retinal detachment, or macular pucker formation, surgery may be necessary.

Medical treatment may be necessary in patients with blood clotting abnormalities.

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections in the eye are currently the treatment of choice for macular edema due to retinal vein occlusions. Injection of steroids in the eye could also be used for refractory and/or chronic macular edema.